SPECTATE: I'll never do what I did yesterday again

SPECTATE is a series of flash essays. It is an evolving record of words concerned with the act of looking.

What colour is the wall?

He told me that nothing is what I see. I write poems in paint, he said. The wall was not white, but shades of white depending on where the light fell.

And then you see.

And then, you see.

Only then can you see - and this is where he lost me.

Perhaps it was because I was tucked safely into the politeness off the room’s gathered audience, or maybe I’d just had enough. I fixed my gaze and let my eyes blur. I tuned my ears to low and gave myself willingly to my imagination. In that fictional womb of protection, I threw my hands up at the talking man and told him firmly that I did not see, and I never would.

It got me thinking, though: If nothing is what I see, then what was it that I saw when the shadow of his pointer finger dried in place on the parquet floor? I know almost assuredly that he pointed his real finger clearly towards the painting hanging on the wall. The shadow only fell short because it couldn’t reach. God gave me the tools to do this, he said, and it was hard to deny that his pointing finger was one of those tools. Yet here we were, a room full of ears, trying hard to decide whether that was a good thing or not. Whether the inch thick oil stuck on the canvas came from his hand, or if it came from God’s.

My arms were waving like heavy flags now. I’d finally lost him.

I want to tell you this, too. A week or so ago I sat in my car and watched a lonely arm wash away heart-shaped condensation from the back window of a school bus. At the time I thought only about the satisfaction the owner of the arm must’ve gotten from doing that. I didn’t think about what the colour of the window was. I knew it was clear in the gaps between the mist building up inside the bus, but I couldn’t tell you the colour of the window where it hadn’t been drawn on yet. Maybe it was marble white or nuclear acid, or a shade of vibrant arsenic in daylight hours.

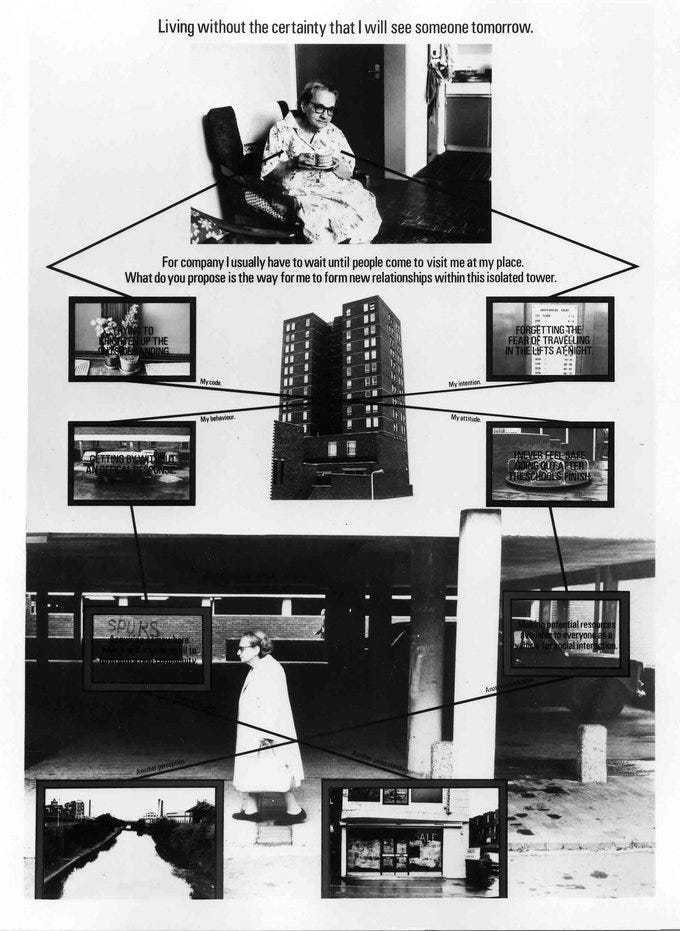

I couldn’t tell you what 1978 means in the context of the Cold War either. But it’s the year Stephen Willats made ‘Living With Practical Realities’, an interrogation of the spatial politics of a block of flats in Hayes, West London. It’s a work about being cut off and confined, restricted and bound. As with much of Willats’ work in that period, it’s also about creating a collective praxis for existing within the physical and social frameworks of tower blocks, dockyards, housing estates and office spaces.

The old lady in Hayes who Willats speaks to, photographs, and constructs reality with lived each day much the same as the one before. At the top of the third panel are her recorded words: “Living without the certainty that I will see someone tomorrow.” It’s clear that she wants to form new relationships, meet other people – neighbours, visitors, passersby – but is so wrapped up in a fear of the outside world that leaving the constructed safety of her home is as much of a death sentence as turning the heating up too high for too long. Lairy children finishing school and lurkers in the lifts at night are equally as threatening an incoming Thatcher government. Isn’t that cruel?

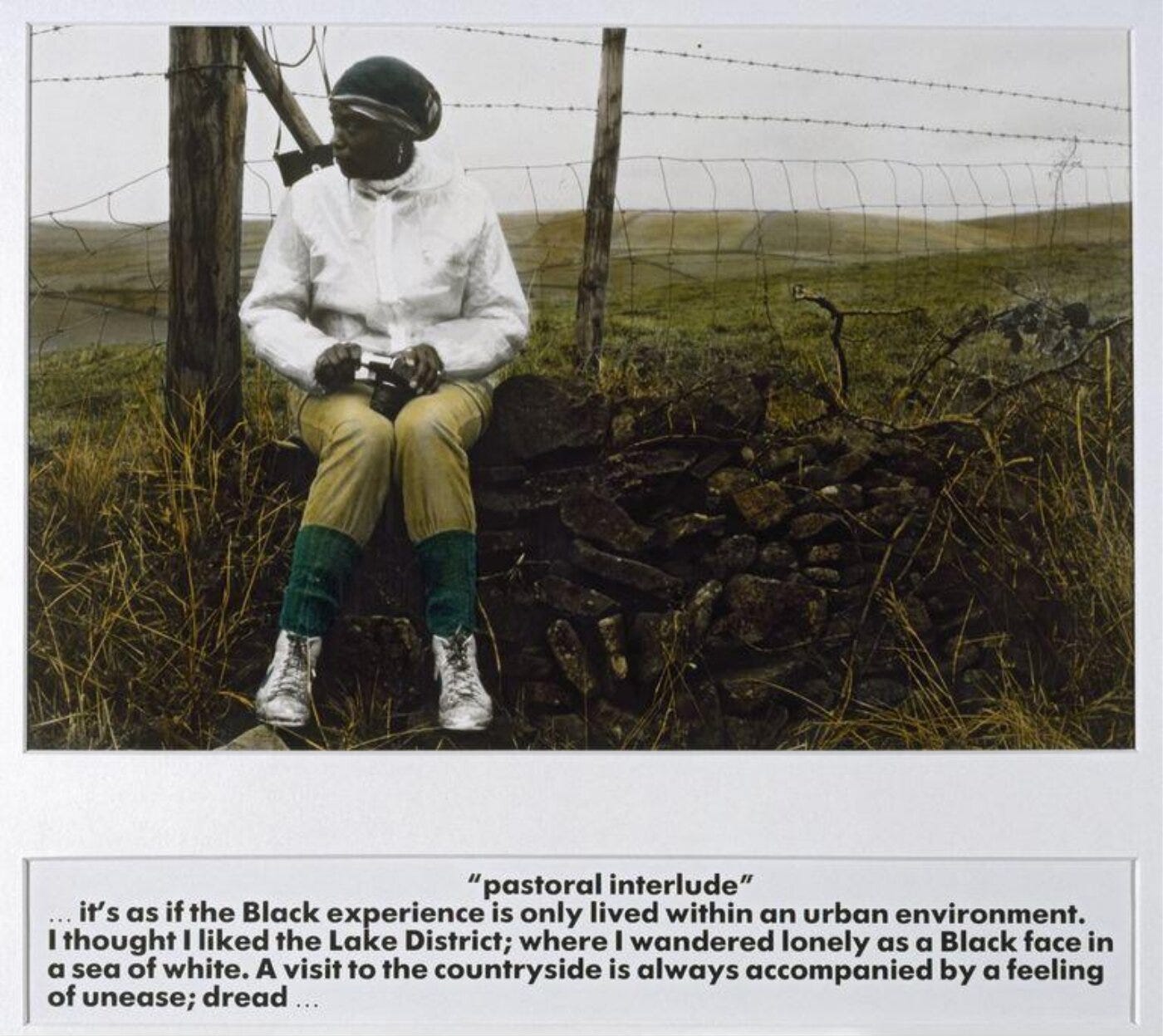

Ten years later, as the Cold War was winding down, Ingrid Pollard examined the Black experience in the English rural countryside. ‘Pastoral Interlude’ shifted blind idealism and naïve romanticism off the kitchen counter and replaced them with the reality of a tense, volatile, and changing social and physical landscape. Using text and photography, Pollard narrated a hidden story of forbidden access in a way that I think Willats does too, though differently. Unseen people are given a voice in both of their works. Their stories are real, complex, and they scream out of the windows in high-rise flats and are spoken firmly from the bowels of uneven mossy hillsides. I read that Pollard took the photographs on holiday in Derbyshire and that they’re happy moments. The text below reveals a deathly cold malevolence lurking beneath the surface, even if the memories are fond.

I often officiate accidental marriages between artists. I’d like to think Pollard and Willats would understand each other deeply, though I can’t be sure. I draw them together because they do not ask what colour the wall is, but instead ask us why it is painted in the first place.

So the bus window might well have been a vibrant arsenic or nuclear acid. It could’ve been both at once, or neither at all. And the wall any colour you choose.

I’m sure that I’ll never do what I did yesterday ever again, so what does it matter the colour of the wall anyway?